wrestling / Columns

The Magnificent Seven: The Top 7 PWI Features

I grew up as a wrestling fan, and am old enough to recall a period before the IWC was even fledgling. In those days, wrestling was delivered via whatever promotions the cable carriers in the area covered, those few instances when wrestling news crossed over into real-world news, and kayfabe-supporting wrestling magazines.

Yes, dirt sheets like The Wrestling Observer have been around for a long time, but it was easy to miss because no major wrestling company was promoting them, so such publications depended upon word of mouth to make their way to fans. Wrestling magazines, on the contrary, were readily available at bookstores, newsstands, super markets, and convenience stores across the country, with full-color glossy photos selling the characters and the action.

My first encounters with such publications were WWF Magazine, which look fantastic, but I soon came to understand that the Apter mags—titles like The Wrestler, Inside Wrestling, and most particularly Pro Wrestling Illustrated (PWI) were more my speed, with a tendency to prioritize text and thoughtful articles (relatively speaking) over the sizzle of exciting photography. I got hooked and had subscriptions to some combination of these magazines throughout my early teenage years, or else bought copies as they hit the newsstands.

In retrospect, and particularly since the advent of the Internet, the magazines seem a little silly, for reporting as if wrestling weren’t based around predetermined outcomes and planned spots. Just the same, there’s a certain nostalgia to them for me, and I suspect many other wrestling fans of my generation and earlier who can still remember the joy of cracking open a new issue of PWI.

So this week, I’m looking back at seven features or aspects of PWI that I found most important, engaging, and entertaining. The criteria is almost entirely subjective on this one, but I have attempted to consider mass appeal (beyond my own preferences) as well as impact on the wrestling fan experience at the time.

#7. Advertisements

Selecting ads as a feature, much less a favorite one, might seem odd, but you have to remember the time and the context. As a fan in the late 1980s and early 1990s, you had WWF and WCW with national programming, and periodic access to AWA, WCCW or the GWF via their less than consistent TV deals. Later, ECW would enter the fray, and other promotions might become available depending on region.

What I’m getting at is that access to news and information about wrestling was predominantly controlled by the wrestling promotions themselves. PWI and the like offered a window into what else was out there. It’s how I learned about tape trading, books, magazines, toys, and merchandise not sanctioned by the major companies, which opened up a whole new perspective on what wrestling could be. In particularly, I recall having my grandmother send off to buy a VHS tape of ECW programming, sight previously unseen, based on a hope that the shows might be good.

Ironically, nowadays I sift and scroll around ads when I catch my wrestling news on the web, but when they weren’t readily available—at a time when fans like me didn’t know what wrestling products might exist in the world—the ads were part of the fun.

#6. Letters to the Editor

Though, in retrospect, I’m dubious all of the letters to the editor in PWI were on the up-and-up (meaning, from actual readers, not written by staff with pseudonyms), at the time they seemed to offer a peek into something like today’s Internet comments sections—a sense of what fans of all dispositions from all different areas of the country were thinking about the current wrestling product and in response to recent PWI features.

Not so unlike the advertisements, today, comments are as much something to avoid as they are to engage with, full of trolls and petty arguments. Just the same, they can also be opportunities for the otherwise voiceless to sound off which, from an idealistic perspective, was what the letters section toward the front of each issue of PWI offered fans—a chance, long before the IWC, to feel like part of a community.

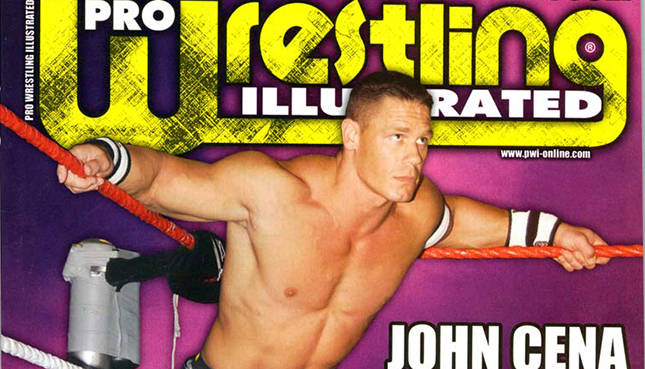

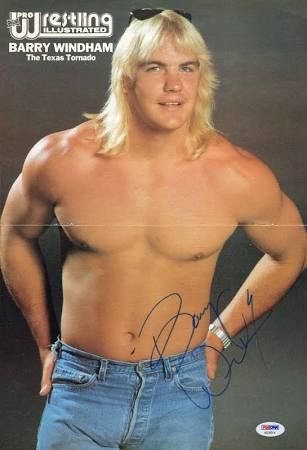

#5. The Centerfold

Traditionally, in the middle of each issue of PWI was an in-depth profile tracking the entire career history of a particular wrestler, and capturing key career details like greatest match and toughest rival, all of which folded out to reveal two-page-sized color poster of the wrestler or team in question.

The poster was a bit of a cheap offering to sell magazines for offering wall art to kids and hardcore fans, and a bit of a tongue-in-cheek nod to adult magazines that used a similar layout for less savory purposes. More so than the poster itself, though, I was a fan of the career summary. Today, WWE.com and Wikipedia nicely cover the overwhelming majority of what these profiles would, but before such tools were available, the profiles offered informative summaries of a career span, all the more compelling because unlike the WWF or WCW, PWI felt perfectly at home acknowledging work in past promotions and past characters—one of the few areas in which the the magazine did blur kayfabe, though they tended to offer rationales as to why the same man or woman had undergone a name and personality change.

#4. Rankings

Each month, PWI shared rankings of the top talents, the top teams, and the most popular and most hated wrestlers in the world, in addition to individual promotions’ top ten wrestlers. In retrospect, I find these rankings to be a pretty cool catalog of wrestlers from particular eras, and it can be fun track guys’ progress not only within any given countdown, but across promotions over the years.

The rankings became even more interesting to me recently. There came a point in my readership when I became less interested in the rankings, convinced they were silly, arbitrary lists rooted in interpretations of kayfabe. It was only in reading Bill Apter’s book from last year, Is Wrestling Fixed? I Didn’t Know It Was Broken! that I learned of his process—calling promoters from different areas to get a sense of which wrestlers were planned to be on the rise or slipping down the card by the time the issue at had hit newsstands, and ranking accordingly—sometimes directly following what the promoters advised, sometimes having to read between the lines from powers that be who didn’t want to explicitly admit that their wrestling wasn’t a shoot.

And so, the rankings captured a sense of where wrestling was and where it was headed, a fascinating mixture of kayfabe, analysis, and creative placement.

#3. Arena Reports

House show results are, by their nature, somewhat inconsequential. They’re booked to please a live audience with the knowledge that, contrary to the millions of eyes on televised shows, only a few thousands will know and remember what happened at them. Nonetheless, it can be fun to have an eye on house show results to track trends, to speculate about special matchups that might get lost for not appearing on TV or video, to get a sense of where the product might be headed based on what a promotion tests out in smaller markets.

Moreover, in the old days before PPV and, more particular for my generation, before PPVs were monthly and the dominant shows around which the product was booked, house shows tended to blow off feuds, as TV got fans hooked and told stories so that we would go to our local arenas and see the feuds play out in live matches.

I may sound like a broken record here, but in the absence of the Internet to track such results and to keep companies honest about wins, losses, and title changes, the “arena reports” were a window into what was happening off camera in the wrestling world, and a fun archive of the different permutations of matchups the major promotions put on at different times.

#2. End of the Year Awards

Each year, PWI published a year-end issue that recognized superlatives like Wrestler of the Year, Match of the Year, Feud of the Year, and Rookie of the Year. The awards were supposedly voted on by readers, and from what I’ve gathered this was largely true—that PWI would collect reader votes and honor their percentages, though the magazine would inflate the voter numbers to make it look like a much larger body of fans had participated (and by extension suggest a larger audience for and impact of PWI).

This feature was less about access to information than an effective archive. I treasured these special issues as a kid for encapsulating a year in which so much could happen and easily have been forgotten, but instead encapsulating the period and both analysis and evaluation of it. Again, this was a period before the Internet, so unless a fan sought to write down the history of every promotion she or he had access to, this was a key mechanism for preserving memories and tracking history.

As a wrestling fan, and one who grew up as a magazine junkie, I still often feel the temptation to look for the wrestling magazine covers when I pass the magazine shelves at a grocery store in an airport. It’s these end of the year awards issues that are among the very, very few that can still tempt me to stop and leaf through, or even buy a copy today.

In fact, I’d say there’s only one annual issue I tend to find more tempting.

#1. The PWI 500

More than any other feature, the PWI 500—an annual ranking of the top five hundred active wrestlers who worked within the past calendar year—was the one to lure me from WWF Magazine, across the indy aisle to PWI. This list functioned as a controversial ranking, ripe for controversy and study, besides which its immensity made it a truly awesome catalog of who was working, including top stars, veterans in the twilight of their careers, and up and comers who just barely cracked the top one hundred—primo countdown territory to suggest a young guy on the edge of signing with a national promotion who would be showing up on national TV sooner rather than later.

Among other things, the PWI 500 is fascinating as an intersection between kayfabe, shoot observations, and playing politics. For example, there were the choices in 1991 not to rank The Undertaker at all and to place Zeus at number 500. In either case, if we were to look at things from a kayfabe perspective, the rankings were absurd, given each man was at or around the main event in the largest wrestling promotion in the world during that year. Meanwhile, from a shoot perspective, The Dead Man’s absence is still strange, but Zeus coming in at 500 doesn’t seem unreasonable, and there’s a fair argument that there were indy workers out there who should have landed safely above him on the list.

The history of the PWI 500 also includes such oddities as guys like Dean Malenko and Rob Van Dam getting number one spots during periods when neither were really in the main event picture, but you also can’t claim that the list was really about top workers when Malenko’s year (1997) saw Lex Luger in the number five spot, and Van Dam’s year (2002) Hulk Hogan finished over twenty spots ahead of Lance Storm.

But the inconsistencies and picking apart the logic have always been part of the fun of the PWI 500, like any other subjective countdown. And placing high on the countdown—particularly the number one spot—still feels like something of a meaningful accolade in a sport full of predetermined outcomes. Also worth noting, after The Garbage Man rode his number 500 ranking all the way to WWF fame as Duke The Dumpster Droese, the last spot on the list became something of a coveted spot in its own right.

The PWI 500 is fun, engaging, and particularly before all the benefits of Internet archiving, an invaluable tool to capture the essence of the business during discreet year-long intervals.

Which PWI features would you add to the list? Let us know what you think in the comments.

Read more from Mike Chin at his website and follow him on Twitter @miketchin.

More Trending Stories

- Janel Grant Files Motion To Strike Preliminary Statement By Vince McMahon In Lawsuit

- Bully Ray Would Not Mind The Rock Beating Cody Rhodes to Win the Title

- WWE Announces Draft Rules & Talent Pools, Champions on Each Brand Are Now Protected

- Kevin Nash Comments On ‘Antiquated’ Oklahoma State Athletic Commission, Thinks Recent Nyla Rose Ruling Was Political