wrestling / Columns

ALL IN and the Future of Fantasy Marketing in Pro-Wrestling Fandom

Wrestling fans used to have a thing called “fantasy booking”, where one would plan out all the elaborate angles and matches required to create dream matches and wild scenarios that only seem possible in a fictional situation, outside of the business logic of it all. Nobody does that anymore. Now what fans do is “fantasy marketing”, where one plans out all the commercial methods a wrestling company can use to produce the most popular product that the greatest amount of people will pay for and thus increase the wealth of all involved – except, of course, those fans.

Examples of “fantasy marketing” for wrestling fans include thinking they understand concretely what creative decisions will increase ratings or sell tickets, claimed knowledge of the formula to get a wrestler “over”, being angry that a wrestler is “ruined” by poor creative decisions, excusing poor output by good wrestlers with “at least they’re getting paid”, any predictions that match to the phrase “the right person won”, arbitrarily chanting “You Deserve It” or “This Is Awesome”, getting excited for new signings from the indies to NXT, knowing the right times to move someone up from NXT or across brands, explaining how certain matches or angles should be held and built to Wrestlemania and/or SummerSlam, and stating without irony or sarcasm that “this is a great time to be a wrestling fan.”

These ideas all represent a belief that there is a clear formula for creating a plateau of generically pleasing content to an abstract audience that will result in miraculously increasing revenue. This is like a logical train track for fantasy marketers, and any kink in the track is a dangerous and ridiculous mistake. Wrestling, like almost all of the creative arts, has very little history of generic formulas equating successful content, even at the mainstream pop culture level. However, as we transaction our way through this century, wrestling pundits and fans tilt ever further towards fantasy marketing ideals, and the American industry has adjusted accordingly.

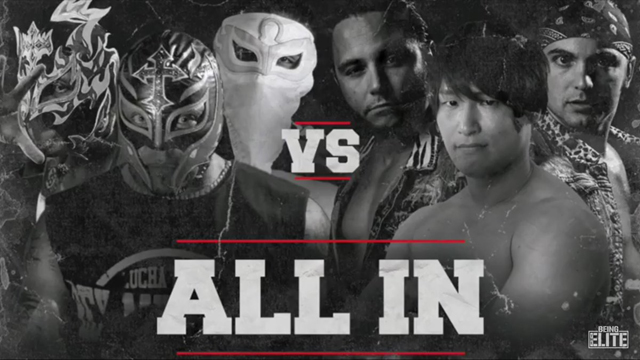

The WWE, in particular, has found a deft way to occupy the mind of fantasy marketers with a dizzying array of seemingly illogical booking decisions, almost like every move by a Roman Reigns or Kevin Owens is another Sudoku puzzle to be solved. Most tertiary wrestling promotions in the US are presented as clones of the WWE and have attempted to follow their lead in hopes of drifting inside that enormous tail of wealth, but the ALL IN event was the most aggressive attempt to independently mine the mentality of fantasy marketing fandom.

While fantasy marketing is about making money, actually (obviously) the fantasy marketer doesn’t make any money if the product matches to their predictions. In fact, they pay money to the companies in hopes of seeing their predictions for that business’s financial success come true. And likely, in order to actually be a successful “creative” business, that company must improvise and adapt, thus rarely realistically living up to the generic standards for success prescribed by the fantasy marketer. ALL IN, however, delivered on its promises just like everyone expected.

This event must be considered successful, both financially from the numbers we’ve seen released since, and creatively based on the overwhelmingly positive response from fans and critics. But was ALL IN a self-contained moment of fantasy marketing meeting real world results? Is the ALL IN business model to create another (well-disguised) clone of the WWE system? Although rarely stated in concrete terms by the public faces of ALL IN, there was an ideological promise embedded in the Being the Elite YouTube series that they are creating an alternative to the dominant mainstream pro-wrestling power. By contributing financially to the Bullet Club’s wealth, you are also investing in a future where wrestling will be different and you will have an option that currently doesn’t exist.

Or was ALL IN just an elaborate scheme by members of the Bullet Club to secure huge money contracts with the WWE? On the Wrestlenomics podcast, co-host Chris Harrington asked:

“What if this is a giant infomercial? And the purpose of this informercial is not starting a revolution and revitalizing professional wrestling, the purpose of this informercial is to invest more and more stock into the marketing potential of the top stars of the show and allow them to negotiate and leverage the best deal possible for them and their families, and their well-being, regardless of how that affects the 10,000 fans sitting in that arena who think they’re getting something else.”

Harrington and co-host Brandon Thurston go on to roughly calculate how little profit was probably made by the main actors of ALL IN, yet hypothesize that this evens out if they are able to sign contracts with the WWE more in fashion with what other superstar athletes make in high profile American professional sports.

The irony is, if ALL IN was just an infomercial for the corporate WWE audience of one, fantasy marketing fans probably won’t be upset. This was always about proving they could be successful business-people, and thus Cody and The Young Bucks have isolated themselves from criticism of “selling out” by storyline-ing their role as producers for the fantasy marketing fans.

On the other hand, the Bullet Club may be on the way to creating a truly open and progressive financial system for pro-wrestling, one that shares profits 50/50 with the performers, provides health care and job security, collective bargaining, and continuing the legacy they began of sourcing what their audience wants and satisfactorily presenting it to them at an affordable price. If so, will fantasy marketing fans find this too ouroboros?

Or is all this indie success really going to satisfy the fantasy marketer? Was ALL IN genuinely a sign that this is “a great time to be a wrestling fan”? Dave LaGreca, the host of Busted Open Radio, thinks so, based on this quote seen in a recent 411 article:

“Think about it: Ring Of Honor at Wrestlemania 33 had 6,000 fans [for Supercard of Honor], and now they’re going to be wrestling in front of 18,000 fans. This is incredible. It tells you how healthy the business is all around. It’s a great time to be a wrestling fan.”

LeGreca here uses a classic fantasy marketer trope: the word “business” as a substitute for the noun “wrestling”, and then blankly assuming that strong business means happiness for wrestling fans. There are many subjectively artistic arguments that can be made against this assumption, the most starkly contrasting being the poor business the WWF was doing in the mid-’90s which led them to shift creative gears and build a new audience with stronger content, and the current state of record profits for the WWE resulting in generally poorly regarded creative output.

This idea also disregards the decades that popular companies in Mexico and Japan have been drawing crowds of tens of thousands of fans, and that content has been always somewhat available to international fans as well. And there was also the peak eras of ECW, TNA and ROH that might not have done a show for 10,000+ people, but were drawing large crowds on sustained tours for years, while also presenting innovation wrestling in the ring and through storylines that had a fundamental effect on the global culture of pro-wrestling.

Fantasy marketing certainly seems to presume that strong business makes happy fans, even with merchandise. During the Monday Night Wars, the duelling successes of the nWo shirt vs. the Austin 3:16 shirt was not normally the source business debate among those adorned in the shirts; guys just wanted a cool shirt for the creative content they watched and enjoyed. The selling of merchandise today for the fantasy marketer is an objective metric to explain the quality of the creative.

For example, indie wrestling news and review site PWPonderings tweeted this a couple of days after ALL IN:

Congrats to @OneHourTees which generated almost a half a million dollars in revenue by selling over 20,000 products according during @ALL_IN_2018

What a great time to be a fan of indie wrestling #ALLIN

— PWPonderings (@pwponderings) September 5, 2018

Again we see the fantasy marketing adage: “What a great time to be a fan of (indie) wrestling”, however this context is rooting for the business success of a periphery merchandising company. It is unclear how this means it’s any better to be a fan of wrestling in 2018 than it was in 2008 because Pro-Wrestling Tees is making a lot of money from t-shirt sales; simply the impressive number alone supposedly equals excellent creative wrestling content. There’s no argument presented that the designs of the shirts, the quality of material, or prices are competitive, just that a company associated with ALL IN was able to replicate WWE-like business numbers.

Questioning the logic behind statements like this may be pointless, as PWPonderings is not responsible for this train of thought; it has been repeated in the textual echo chamber of social media that brings beliefs into pop culture reality. No one can deny that many expensive t-shirts were sold, tons of fans traveled to and enjoyed the ALL IN show, and you’re hard pressed to find anyone willing to complain about any of it. Everyone is happy, everyone is getting paid, and it’s “never been a better time to be a wrestling fan”.

However, the western intellectual has often approached blind happiness with suspicion. They have been trained to see religions and cults as requiring deeper investigation because it is believed that no one should be that happy. This is especially true when the measure of capitalism is applied to the situation. A religion professional or cultist talks about the power of an intangible “god” while collecting tangible wealth from the majority of their audience. Those people are left without some of their money and convinced to be happy about it, and maybe they are.

Was the spectacle of ALL IN enough? For the fantasy booking fans of old, I would think it was an amusing a night of simple fun, neat storyline pay-offs, and fine wrestling matches; but it could have been better. For the fantasy marketing fans of today, where creative content is secondary to business justification, I wonder if they believe this was truly the beginning of an eventual shift in power for their industry?

Nike recently used the image of former NFL player Colin Kaepernick in their new Just Do It ad campaign, not due to his excellence on the field but because his aura of activism for change was a more marketable quality. Similarly, The Young Bucks and Cody promised to create something new with ALL IN, implying that they were doing more than just putting on excellent matches but were starting a revolution in pro-wrestling. The art of wrestling, much like the sport of football with Kaepernick/Nike, was secondary to using ideology to sell a product. Whether ALL IN or Nike can actually produce any tangible changes is an unknowable, abstract future; however, the immediate wealth earned by the actors in this situation is undeniable. And where that money comes from is the people who gain the least from paying out for the product, and lose the most when ultimately nothing changes.