wrestling / Columns

Going Broadway 05.08.12: The Picaresque Journey of Orville Brown

July 14, 1948.

A conference is called by Sam Muchnick at the President Hotel in Waterloo, Iowa to discuss the formation of an alliance between six of the wrestling territories in the United States. The idea, of course, is to generate more money for all by not remaining fractured and isolated but by unifying and sharing talent under one banner.

What Muchnick and the other promoters did not realize that day when they formally created the National Wrestling Alliance is that they set into course the framework for the professional wrestling business that would remain the norm until the WWF’s explosion as a singular national promotion in the 1980’s.

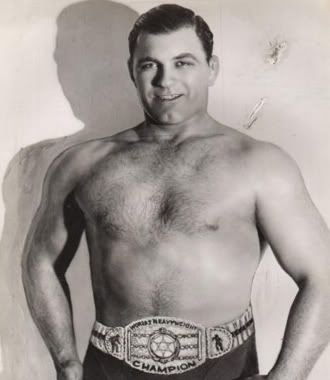

One of the final orders of business that day was to decide who to put at the forefront of this new alliance. A champion. One to carry the banner of this newly formed NWA to territories from coast to coast and create a strong and growing fanbase. The man they turned to that day was in the room with them, a booker himself from the Kansas City territory, but first and foremost a wrestler from Sharon, Kansas: Orville Brown.

On that day, Brown would enter a special and irreplaceable part of a lineage that would span to Colt Cabana today: He would become the first recognized NWA World Heavyweight Champion.

…

To say Brown’s early life was something out of Steinbeck would be an understatement. Growing up in Sharon, Kansas, Brown was the youngest of five and quickly found his upbringing relegated to hard work in the fields on the family farm. His father, in a circumstance of a different era of America, was forced to leave town due to death threats from his in-laws.

Rallying around their mother, the children pulled together with their labor to try and keep the family afloat. Everyday, Brown had to journey nearly 20 miles to the town of Kiowa in order to attend school. Because of his family’s hardships, though, Brown only lasted one year in high school before dropping out to work full time.

Although his athletic career in high school was abbreviated to only his freshman year, Brown’s size and physique combined with an obvious athletic talent, earned him a starting spot on the football team, and after he left high school, he found more than moderate success as a rodeo cowboy.

The money, though, in being a rodeo cowboy was not considerable and having recently eloped with the land owner’s daughter, Grace, and becoming a father, Brown was having to work twice as much to make ends meet.

Twenty one and being a dad in the Great Depression can grizzle any man, but Brown kept steady employment in the fields and when the harvesting season was over, he found work as a blacksmith. In 1931, he became his own kind of local folk hero when an overwhelming snow storm hit the area, and Brown braved the harsh conditions to transport coal from Wallace to Sharon Springs to supply the town.

A chance meeting between Brown and another Brown, actually, Ernest, (no relation) became a turning point in 1931. Ernest Brown was involved in the local wrestling scene and was impressed with Orville’s size. He convinced him to give wrestling as a try to possibly earn some extra money for his family.

Brown took the training very seriously, having had no prior wrestling experience, and traveled to the local high school in Wallace every day after working in the shop to hone his new craft.

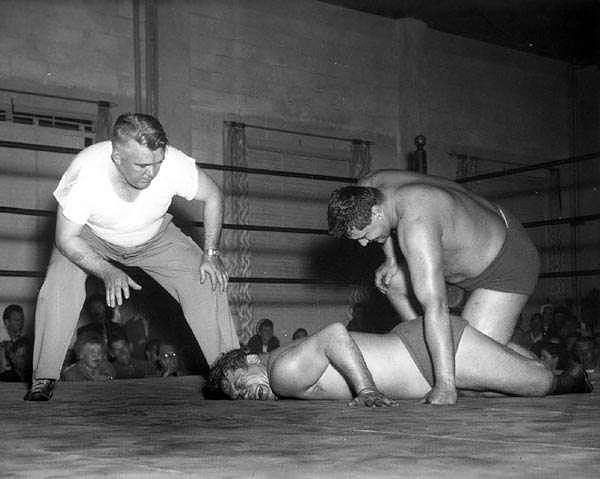

But this was not the professional wrestling that we have come to know today that Brown was entering. These were paid shoot bouts that relied purely on amateur wrestling skills. No matter. Brown became a dominant prodigy at age twenty three. He became his own legit Goldberg, winning an astounding seventy two consecutive matches.

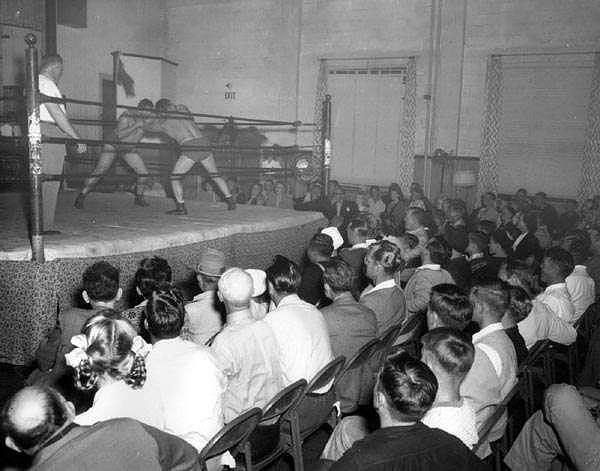

His popularity and success earned him his first exposure to the spectacle of professional wrestling where faces and heels were prevalent and the finishes were planned and worked out before hand. His shoot bouts served as frequent undercards during the Wichita shows, providing Brown exposure to another facet of the wrestling business; one that could prove to be more lucrative than what he was already involved in.

Brown traveled to St. Louis where he showed considerable promise in a try out for the local promoter. He sent Brown to Baltimore to train under George Zaharras and work undercards in the area to gain seasoning and more exposure before he returned to the Midwest.

By 1934, he was touring the States and proving to be an excellent foil to heel champion Jim Londos who he feuded with in cities from Atlanta to Detroit, coming up short in all bouts but showing a toughness and endurance as matches went easily forty minutes to an hour on the average.

An example, in June of 1935, Brown and Londos went seventy three minutes before Londos won by a pinfall to crowd of over 11,000 in Detroit. A footnote to this show was the fact that Lou Thesz made his professional debut on that same card.

With the considerable income he was acquiring through wrestling, Brown was able to purchase a farm of his own just outside of Kansas City. Finally, his own pocket of land. But the journey still had many turns in its path before he would settle down.

…

In 1936, the loose confederacy that kept the wrestling territories semi-united under the banner of one world champion began to fracture when Dick Shikat did a shoot on Danno O’Mahoney and stole the world title front of the Madison Square Garden crowd. This began a chain of events that caused territories to segregate themselves from other territories and crown their own champions.

This caused the popularity of wrestling to dip because instead of nationally recognized story lines and champions, now every region had their own of each, leaving the fans in limbo of what to follow.

Nevertheless, Brown continued to be a draw in many cities and territories. In Memphis, he carried on a successful feud with Ray Steele throughout 1936 as well with O’Mahoney, Dean Detton, and Vincent Lopez. By 1937, he was working predominantly for the Midwest Wrestling Association back in Kansas City.

From 1942 to 1948, Brown would reign eight times as the territory’s world champion and even extend himself into booking to help the promotion as well. With his immense popularity and good reputation on the east coast, he was able to negotiate many appearances by name wrestlers in the Midwest, which made Kansas City an even more sustainable crown jewel of the wrestling territories.

Miles away in St. Louis, a full blown cross town promotional war was taking place, as Sam Muchnick, disgruntled over the pay he was receiving despite his hard work for Tom Packs, was beginning to run his own shows consistently under his own banner. But Lou Thesz, who had been a top draw for Packs in his shows was now positioning himself with a host of investors to buy out Packs’ promotion. Muchnick sensing a larger move to overwhelm out of the territory launched his preemptive attack with the gathering of other Midwest promoters that fateful day in Waterloo, Iowa.

When Brown became the newly formed NWA’s World Champion, he began touring the country from coast to coast as the face of not just a territory but as the ambassador of a stronger, more sustained wrestling force that, along with the increasing use of television, made the sport popular again with fans nationwide.

But in St. Louis, the battle between Muchnick and Thesz was becoming a perilous stalemate with each losing out on potential big gate returns because of their shrewd undercutting of one another. (This territorial war was also the perfect breeding ground for Buddy Rogers who was a major draw for Muchnick in St. Louis.)

Realizing what profits were being lost, an amicable détente was reached between Muchnick and Thesz which would lead to a negotiated merger between the two promotions. The unification would be cemented by a battle of their respective world champions, Brown (representing the entire NWA) and Thesz, himself. A match was put into motion to take place on Thanksgiving night in 1949.

The plan was to have Brown go over on Thesz that night and then put Thesz over in 1950 to give him his run as NWA champion. But sadly, the match would never take place.

On October 31, Brown and in-ring rival/best friend Bobby Bruns were traveling from a show in Des Moines when they collided with a stalled trailer truck, crushing the car. Bruns broke his shoulder but was able to maintain consciousness. Brown, on the other hand, was violently struck in the head and collapsed soon after emerging from the wreckage.

Brown would remain in a coma for five days.

…

Although he came out of his coma with full faculties, Brown’s left side remained paralyzed. Realizing the grim outlook for the in-ring career of their champion, the NWA placed the World Title on Thesz without their epic unification match ever taking place. Thesz’s first reign as NWA World Champion would last for the better half of the 1950’s.

Brown eventually regained the feeling in his left side and attempted to make a comeback, but the reality was, his body was never the same again after the accident. He would withdraw from wrestling in 1957 after trying to manage his son Richard’s short lived wrestling career.

He and Grace would later settle into a retirement village in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, enjoying a steady life of outdoor work and recreation, just like his days long ago growing up in Sharon. On January 24, 1981, Orville Brown passed away at age 72, leaving behind a picaresque life of Depression Era mettle and pioneering in-ring charisma and skill. The fact is, you’ll probably never see him on any wrestling fan’s top ten list, but his place in the NWA is definitive: he was the first.