games / Columns

Eye of the Beholder Directors Discuss Telling the Story of D&D’s Art In New Documentary

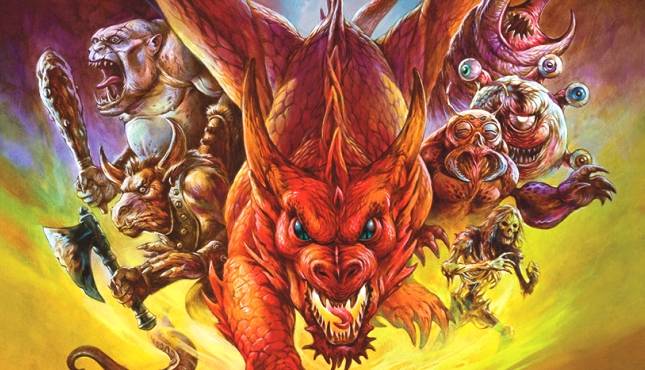

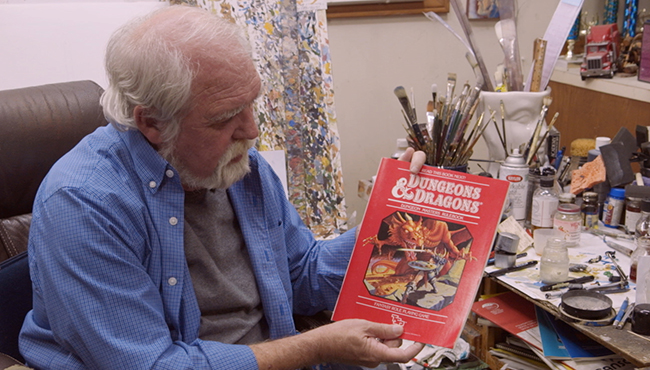

Image Credit: Jeff Easley & The Nacelle Company

Image Credit: Jeff Easley & The Nacelle Company

As iconic of a roleplaying game as it is, Dungeons & Dragons has influence well beyond phrases like “critical hit” and alignment charts. In addition to its impact on the fantasy narrative genre as a whole, granddaddy of tabletop RPGs has long been an influencer in the world of art as well. Most of what we know of modern fantasy art finds its roots in D&D, which brought in, cultivated and gave the world some of the most well-known fantasy artists (and art pieces) of all-time.

For years, while there has been plenty of focus on the creators and developers of Dungeons & Dragons — Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson, Frank Mentzer and so on — it seems like the artists don’t always get their due. Not that there aren’t hefty fanbases for the works of Larry Elmore, Jeff Easley, Clyde Caldwell, Keith Parkinson, Brom and many others, but there are times where it seems like they don’t get quite the credit they deserve for adding an essential element to Dungeons & Dragons in the artwork, allowing fans to know what the monsters really look like and thereby shaping an entire direction of the art world.

Eye of the Beholder: The Art of Dungeons & Dragons helps to rectify that oversight by examining the art of the game’s forty-plus year history and shining a spotlight on those artists who added an essential part to the game. I had the chance to Brian Stillman, Kelly Slagle, and Seth Polansky, who respectively co-directed and produced the documentary, about creating the film, finding the balance between reaching old-school fans and new players, and more.

What inspired you to make a film about Dungeons & Dragons’ art?

We’ve all been playing D&D for years—Seth and Brian have been playing for decades. And we always thought the art was as important as the game itself. Artists like Dave Trampier, David Sutherland, Jim Roslof, Erol Otus, Jeff Easley, Larry Elmore, Clyde Caldwell, and the rest had the power to transport people to other worlds, and their work was utterly captivating. We realized that a lot had been written about the history of the game itself, and its creators, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, but there wasn’t much about the art. Since we’re all filmmakers and journalists, we decided to partner up and tell the story ourselves.

Eye of the Beholder ends up sort of telling the early history of D&D, something I really appreciated as a long-time player. Was that something that you initially intended to do, or did that just naturally develop?

We knew that a bulk of the movie’s narrative would center on the early days of the game and art and artists. In the late Seventies, it was all so new and fresh; the only place to find fantasy art, really, was on the covers of paperback novels, some record sleeves, and the occasional Lord of the Rings calendar. Big books of fantasy weren’t being published and the Internet was a long way off. Museums or galleries dedicated to genre art weren’t anywhere to be found. So, in so many ways, D&D was creating the market on the fly. That gave us a lot to explore, and in doing so, we definitely decided to at least touch on the early history of the game as a whole, if only to provide context.

As someone who’s been playing D&D since the early 1980s, the stories about how integral the art was to the game really resonated with me. I know you’re also long-time D&D players. I’m sure narrowing down to your favorite piece is probably impossible, but do you recall the piece from your early days first really struck you and drew you into the game?

BRIAN STILLMAN: Narrowing it down is really hard, there are so many amazing pieces across so many years. But early on I had one favorite piece that I always came back to. There was a black-and-white illustration by David C. Sutherland III in the first edition AD&D Player’s Handbook called “Paladin in Hell.” It shows a paladin in full armor and a glowing sword standing on the edge of a cliff, squaring off against a horde of devils. I was struck by how alone he looked, and I was a little freaked out as a kid at the idea of wandering the entire length and breadth of the infernal plane, enemies all around me, just struggling to survive. But it also inspired me with the storytelling wrapped up in that one image, and it helped shape my interest in fantasy and gaming as I got older.

KELLEY SLAGLE: I’m newer to D&D, having played only for the last five years. I discovered my favorite piece of D&D art while editing the film. I’m a huge Brom fan, and I was blown away by a painting he did for Dark Sun of a fighter fighting undead on a bridge over the stark landscape. In fact, the entirety of the Dark Sun body of art that Brom did resonates with me.

SETH POLANSKY: Definitely the “red box” cover from the D&D Basic set. That’s the first D&D product I owned, and Larry Elmore’s art is the reason why I begged my parents to buy it for me! The story Larry tells in the movie, about Gary Gygax directing him to paint something for the cover that will “reach out and grab ya,” did exactly that!

D&D is in the midst of a pretty major resurgence over the last several years, and the film is adept at presenting itself both for old-school fans and those who are new to gaming. How did you go about achieving that finding that balance?

Dungeons & Dragons art is a continuum, not a moment in time, and we wanted to capture that. While a lot of people think of the art in terms of the Eighties—when the game was just dominating sales and people like Larry Elmore, Jeff Easley, Clyde Caldwell, and Keith Parkinson were defining the idea of fantasy art—we wanted to also show that the art is a living thing that continues today. New artists and art directors and designers are pushing it in wonderful directions that are just as exciting and fun and epic as anything done in the last 40 years. It’s all D&D art.

We made it a point to interview as many early artists as we could find, but also newer artists working on the game today. We interviewed fans with a lot of history playing the game, and fans who’ve gotten into it more recently. We spoke to art directors who’ve been with the game through many editions. We tried to bring in perspectives that run the gamut of all D&D’s many eras to help tell this story.

You have so many significant figures in D&D’s history that appear in the documentary, and there was a ton of history to boil down into a single film. Were there artists or other people that you wanted to interview but weren’t able to speak with?

When making this kind of movie, you’re always going to have a wishlist of people you couldn’t include. Sometimes it was because they never got back to you or you couldn’t track them down in time; and in some cases, you reach a point where you risk over-stuffing the movie. If you have too many people, nobody has any room to breathe. That’s probably the most difficult part of making the documentary, deciding when you’ve got enough to tell the story and drawing the line and saying, “We need to stop shooting and get this thing done.”

That said, we tried to showcase as much art from as many different artists, from staff to freelance, as we could. And we made sure to credit them all on-screen. We wanted to show how many people really contributed over the years.

There are some fascinating stories that come out in this film, such as how a lot of the art was very nearly lost several years back. What was your favorite anecdote from speaking to everyone?

We got a lot of great stories. One was given to us by the artist Diesel LaForce. They used to have these rubber-band fights in the art department and one day a shot went wild and the rubber band went skipping off one of Jeff Easley’s paintings—and it was still wet. It left a big smear. Luckily, Jeff had gone to lunch or something, so one of the artists rushed over and actually fixed Jeff’s painting. Jeff came back and apparently he didn’t even realize it

Then there was the time Larry Elmore came into the office and discovered all his stuff was missing. He couldn’t figure out where it went. He flopped down in his chair, leaned back with a sigh, and glanced at the ceiling—only to find all his stuff, from paintbrushes to his phone to his notebooks, stuck up there. Keith Parkinson liked to play practical jokes and apparently Larry was the target of the day.

As expansive of a story as D&D’s art is and as well as the film covers it, there are still a ton of stories that could be told within the gaming industry. Do you have any plans for any other gaming-related documentaries or projects?

We’ve got a few things that we’re exploring, but they’re still in the early stages. We’ll be sure to let everyone know once we move into production! We’re pretty sure fans of this movie will like the next one, as well.

What’s the one main thing you’d like have people to come away with after watching Eye of the Beholder?

We hope that people will get a new appreciation for the artists, and for where the art comes from. We hope they’ll understand that they art wasn’t just designed to pretty-up the books, that it’s an integral part of the game, part of what made it popular, and part of its history and legacy. These drawings and paintings have had a profound influence on fantasy art over the last 40 years, and the artists behind it all are overwhelmingly talented and imaginative people who continually push the genre in new and exciting directions. It’s still inspiring people today.

I’d like to thank Brian, Kelly and Seth for taking the time to answer my questions. Eye of the Beholder: The Art of Dungeons & Dragons is currently available on a varity of services including Amazon Prime, Comcast Xfinity, Google Play, iTunes, Vimeo, Vudu, Sony Playstation, Xbox, YouTube and cable subscriptions. You can find out more about the film here.