music / Reviews

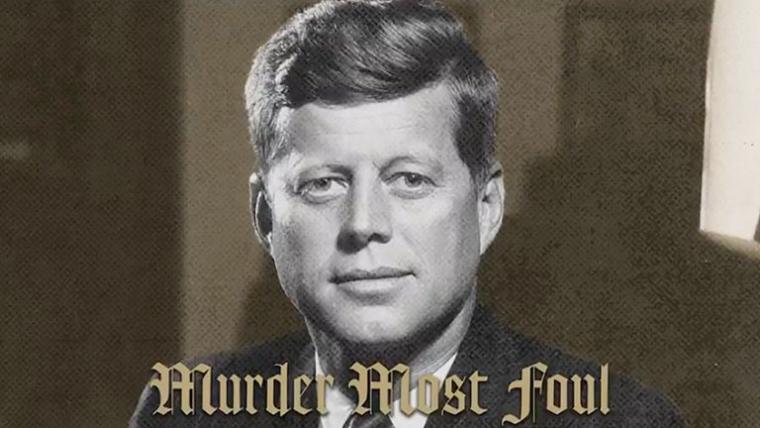

Bob Dylan – “Murder Most Foul” Review

Bob Dylan has always been a sharped edged, sardonic and aloof character at the best of times: a barbed tongued and quixotic poet who interlaced cruelty and kindness so seamlessly that his sarcasm and sincerity became indistinguishable. Fittingly, in wonderfully ironic turn, when Dylan was shockingly awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016, he was in the midst of a deep dive into the American songbook. The United States’ great songwriter, poet and social critic had seemingly given up on writing original material. Dylan released three straight albums that teased out the rich undercurrents of his own music – the early inspirations that were escaping our thoroughly modern memories. His own crooked and warped croon was now weaponized as Dylan explored ballads and story-songs of Sinatra, Berlin, Rodgers and Hammerstein on cover collection after cover collection.

The Nobel Prize is of course a lifetime achievement award. Dylan earned it across a number of remarkable purple patches stretching from his stunning sophomore effort The Freewheeling Bob Dylan (1963) through his psychedelic-estrangement (Blonde on Blonde) plunge into country (Nashville Skyline), an array of dense detail laden narratives (Desire) and his Christian rebirth (Slow Train A Coming). Even when he embarked on his vocal shredding Never Ending Tour and plunged into the critical nadir of the late-80s, Dylan surprised the world by rediscovering his finest fettle as the millennium approached. 1997’s Time Out Of Mind and 2001’s “Love And Theft” proved that age could not dent either Dylan’s poignancy or potency – and, against all the odds, by 2006 he was cool again. Modern Times soundtracked an iconic advertising campaign for Apple’s iPod as Dylan’s lyric sheet proved eerily prophetic, outlying the social critiques (working class Americans losing their jobs and communities to Globalization) that would go onto to define the next decade of political upheaval.

Regardless of his achievements there’s no denying that Dylan feels distant in 2020. He’s still out there, roaming the world, croaking his way through his classic catalogued reimagined by an ultra-tight Americana bar band in any and every country that’ll have him. He was so busy in fact, that he didn’t find the time to accept his Nobel Prize until 2017 and nearly lost the $900,000 prize in the process. Dylan might be off in a world of his own, but Covid-19 has put an end to the Never Ending Tour. Borders are sealed, concerts are cancelled and Bob Dylan, at 78 years of age, is a very much at risk.

It is into this void that Dylan slipped “Murder Most Foul” on YouTube. Ostensibly a gift to his fans, at 16 minutes and 58 seconds it is the longest song that Dylan has ever released. This is brand new material to the listening audience, but according to Dylan it is an old unreleased effort. In a bizarre twist of fate, a brand-new, long-abandon relic of Dylan’s oeuvre is set to secure his first ever Billboard No.1 Single (in 2020 of all years!).

“Murder Most Foul” is a curious proposition. The story of a bloody murder: an ode to bonefide national tragedy that nevertheless comes steeped in reverential nostalgia for a golden age of Americana. It’s tempting to compare this story of President Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas with “The Hurricane” (or another of Dylan’s long form narrative works), but the comparison simply jars. Dylan isn’t weaving an angry, impassioned and knotty start-to-finish tale, instead “Murder Most Foul” lilts, saunters and slips into a pillowy haze. Soundtracked by a gloriously hesitant piano line and a warm-yet-funereal violin, Dylan mixes factual narrative detail with long reveries in what quickly becomes a love letter to our rose-tinted pop-cultural romanticism for an era fraught with tension and violence. Immaculate fantasy underwritten by brutal reality.

President Kennedy is served up like a sacrificial lamb, both to fate and pure circumstance, but also to the cultural moment. “Was a matter of timing and the timing was right”, Dylan has an incredible ability to codify the strangeness of the moment: the sheer shock horror, the confusion and the absurdity of the President being inexplicably assassinated in front the world’s eyes: “The day they blew out the brains of the kings/Thousands were watching, no one saw a thing”. The American public had a front row seat to their own bamboozlement.

Dylan’s turn of phrase is sumptuous as he mixes brutality with cosy nostalgia. If the song can be defined, it is with the image of Kennedy lying with his brains splattered in the back of ambulance, speeding hopelessly to Parkland hospital and somehow listening to Wolfman Jack playing the sounds of the rock and roll revolution (past, present and future) on the car radio. Kennedy slips not into misery, although there are plenty of irrepressibly bleak moments, but into a glorious reverie fuelled by a pop-culture about to enter a globe conquering golden era.

“The Beatles are coming, they’re gonna hold your hand/Slide down the banister, go get your coat/Ferry cross the Mersey and go for the throat”. Even in this celebration of The Beatles’ conquest there’s a brutal, cynical edge and that tension stalks “Murder Most Fouls’” entire 17 minute run time. Even seemingly innocuous couplets are sung with a crooked smile, “I’m going to Woodstock, it’s the Aquarian age/Then I’ll go over to Altamont and sit near the stage”. Of course, had Dylan sat by the stage he’d likely have been smashed in the face by a Hell’s Angel as Altamont’s love-in turned sour.

All this beauty, what many baby-boomers (and beyond) consider a true culture-defining peak, occurred in the shadow of such violence and social carnage. Perhaps Dylan’s point is the exact opposite: pop music doesn’t live in brutality’s shadow, but instead it shines a sanctifying and sanitizing light on our shared history. Maybe we are attending the “party going on behind the Grassy Knoll”: a President can be executed as if by magic and we go back to dancing and singing and living our lives, unquestioning and, by and large, unaltered.

Dylan is clearly having an absolute riot stringing these sneakily conversational rhymes together. On occasion he gets a little carried away (“I’m just a patsy like Patsy Cline”), but more often Dylan pens lyrics that are simply serene on the ear. No singer, past or present, has better understood how to wring every last ounce of empathy, irony, anger, disgust, disinterest and sentimentality out of their raw vocal tone. Dylan ends line after line in with these wonderfully idiosyncratic phrases that are pleasure to imitate as if they could only be sung in Dylan’s own distinct drawl-cum-croon (“but his soul was not there, where it was supposed to be at/For the last fifty years they’ve been searching for that”).

Whether twisting the knife or drifting away into an angelic haze, Dylan’s tale is intoxicating, even as he devolves into pure abstraction. The longer “Murder Most Foul” runs (and as Kennedy’s soul escapes his body) the faster the structure of the narrative dissolves until Dylan is left listing great songs, musicians, films, actors and everything in between. Kennedy embraces the afterlife, Lyndon B. Johnson is sworn in and we enter “a slow decay” drowned out by the most beautiful music and unforgettable imagery.

“Murder Most Foul” feels utterly essential precisely because it drifts so serenely. Kennedy’s assassination plays like a collective daydream or an improbable magic trick: something visceral, bloody and heart-breaking is transformed into a shimmering reverie. Dylan’s anger and disgust are unmistakable, even on such a loving and tender composition. He never seethes and his rage deftly supressed, instead “Murder Most Foul” is one long beautiful toast to having the wool pulled over our collective eyes. We live in the afterglow of bloody murder: brains splatter as we dance, drink, sing and fuck our way to an imagined immortality. There’s nothing wrong with that, it provides a worthy escape – as Dylan imagines it did for Kennedy himself – but it doesn’t change the fact that a man has been killed in cold blood and we are none the wiser.