Movies & TV / Columns

Tom Huckabee Sits Down With 411 to Discuss His Movie Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited

The 411 Interview: Tom Huckabee

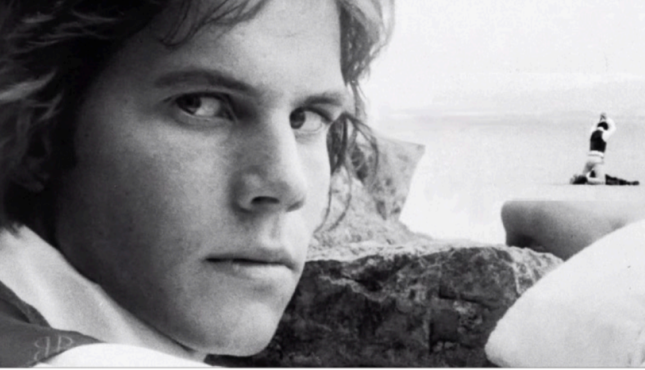

Tom Huckabee is a writer, director, and producer who has been working in the entertainment business for over four decades. He has directed the short films Death of a Rock Star and The Family Cowsill, the documentary short Confessions of an Ecstasy Advocate, and the feature film Carried Away. Huckabee has also written the screenplay for the action movie Rage and has written for the TV show Ghostbreakers. Huckabee is also the founder and president of Gold-Alchemy, a sort of artists organization (check out the Gold-Alchemy website here). Huckabee’s latest effort is Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited, a fascinating low budget arthouse post-apocalyptic sci-fi movie starring frequent artistic collaborator Bill Paxton that’s actually a reworked version of Taking Tiger Mountain, which received a small release in 1983 (check out my review of Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited here). In this interview, Huckabee talks with this writer about making Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited, the movie’s potential meaning, and more.

**

Bryan Kristopowitz: How did you get involved with Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited?

Tom Huckabee: First, thank you for your interest, Bryan. I met Bill Paxton on a plane from DFW to London on March 1, 1973. I was 17 and a junior in high school. He was 18 and already graduated. We were part of a group of 20 kids from two different schools in Fort Worth—where we were both born and raised—who were enrolled at Richmond College, an American liberal arts college affiliated with the University of London. I was going to be getting high school credits while Bill would earn college credits, although we shared several classes together like art history, drama appreciation, and creative writing.

Two weeks after arriving at Richmond, I received a letter from home that I’d won first place in the high school division of a film festival held at Texas Christian University. Enclosed was a certificate and a check for $50. Bill was impressed by this. He had made a couple of Super 8 films for classes at Arlington Heights. Four months later, we reunited in Fort Worth and together purchased Kodak’s new Ektasound Super 8 movie package. We wore the motor out of the camera making movies for the next six months. Until Bill’s dad, John, a lumber magnate and art collector, bought him a one way ticket to Hollywood and sent him off with letters of introduction. I tried to talk him out of going, which fell on deaf ears. Bill loved adventure, travel, and physical challenges. (I didn’t.) He asked me to come with, but I was still in high school.

Right away Bill scored a good job at Encyclopedia Britannica Films and was assigned to assist a young writer/director/producer of educational film, Kent Smith, who had studied at the UCLA film department at the same time as Francis Copolla, The Doors, and George Lucas, if I’m not mistaken. It was only months after meeting that Bill and Kent shot an experimental short on black and white 16mm, entitled D’artangan and starring Bill. Then Kent wrote a feature script for Bill to star in, loosely based on the kidnapping of John Paul Getty III, crossed with Camus’ The Stranger and set in Tangier. They rented an old 35mm Arriflex camera from Byrnes and Sawyer, adapted for Techniscope, and bought all the b&w 35mm short ends left over from Bob Fosse’s Lenny ( facts that have caused me years of annoyance, as quite a bit of the footage was tainted by static electricity burned into the negative.) They flew to Spain, rented a car and ferried across the Mediterranean to Morocco, where they were immediately incarcerated for not having obtained permission beforehand to bring film equipment into the country. After a couple of days Kent bribed their way out of jail. Back in Spain and down on their luck, Bill remembered he had friends in Wales, whom he’d met at Richmond College. They drove to Wales and spent the next six weeks casting and crewing and running and gunning, rewriting the script for the new locale and the nonprofessionals they were hiring to act alongside Bill. They ran out of money after shooting about half of script.

Meanwhile, back in Fort Worth I graduated from high school and headed to Hollywood at Bill’s urging. We all ended up in LA at the same time. Bill immediately went to work as a set decorating Jonathan Demme’s Crazy Mama. A few days later ten big boxes of negative and work print arrived from England. I got to watch it in the projection room at Encyclopedia Britannica. I don’t think Bill even got to see the dailies because he was working. Kent tried for years to raise money for them to go back to Wales and finish the film to no avail. Bill moved to NYC to go to acting school. And I relocated to Austin, Texas to go to film school. Three years later in my senior year, I wanted to make a feature, and I wanted to do something post-apocalyptic. I optioned an award winning short story called Mary Margaret Road-grader by Howard Waldrop but couldn’t raise the money for production. Meanwhile, the film department had acquired a used 16/35mm Steenbeck Flatbed that no one was using. I convinced Kent Smith to lease me the footage and my professors to give me the flatbed.

BK: How did you create Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited out of the original footage shot by director Kent Smith and Bill Paxton?

TH: First I watched it all again and catalogued it. I had their script and assembled the dailies accordingly, until I had about 50-60 minutes of silent film that flowed well visually, albeit with quite a few dialogue sequences, which had no sound. I knew I couldn’t go back to Wales, so I brainstormed with associates about what to do about. It. We rewrote the story and gave it a post-apocalyptic setting. Then we came up with an idea for a wrap around for the story about a team of feminist terrorists training a young American draft dodger to murder the head of prostitution in a small village in Wales.

Kent had also sent me the 16mm unedited footage form D’artangan and I got the idea to make it into a film within the film about brainwashing and programming Paxton’s character. We shot a ten minute opening sequence and built an ending section out of sync sound footage Kent had shot a year later during a second trip to Wales, regrouping the original actors, everyone but Bill, who was in school at NYU. But this only gave me about 65 minutes altogether. I needed another 10 minutes at least for a feature. So, I built 10 minutes of dream sequences from out-takes. Then I rewrote the script to match the new concept and started dubbing the dialogue and building the sound effects and music from scratch.

BK: What was the original intention of the footage that Kent Smith shot? Is the movie that currently exists close to that original intention or did you, essentially, create something new out of it? What was left on the cutting room floor?

TH: “Arf” and “arf,” I’d say. I used as much of their footage and story as possible. There was next to nothing left, footage wise, just extra takes of the stuff I used. But since they only shot half of their story, all the new stuff was totally new. And then we added the extra layer of radio broadcasts, shot the inserts of loud speakers to match the original footage to sell the idea that the authoritarian government of the future was broadcasting propaganda 24/7.

BK: How was the movie changed since its original screenings after the movie was completed in 1983?

TH: Every foot of film and each second of sound was reevaluated. All scenes

were tweaked, some were cut in half, a lot of weather and set decoration was added with After Effects software. The first ten minutes and last ten minutes were given the most scrutiny. The new scene after the credits was shot by me with an iPhone 7. The new and awesome end credit tune, “Kill All Men,” (written by Dan Puckett, a member of my 1970s punk band The Huns and a member of Radio Free Europe, who supplied the rest of the soundtrack on TTM) was rearranged and recorded by Andrew Todd Rosenthal, who had been partners with Bill Paxton in the video band Martini Ranch, circa 1987. TTMR at 76 minutes is eight minutes shorter than TTM. I think it’s easier to follow and emotionally more accessible. Less nihilistic.

After I graduated from UT, I was still far from finished but I’d managed to find an investor to put up $30K, which allowed me to move to LA, rejoin with Kent and he helps me finish it according to my vision. It came out better than anyone expected and I secured a distributor who was handling Penelope Spheeris’ seminal first feature, The Decline of Western Civilization. Meanwhile, I got a job at Landmark Theaters and they put the film on their circuit. We had a great first weekend selling out the Roxie in San Francisco and got good reviews there. But that was the highlight of the initial release.

I came down with appendicitis during the domestic release and the distributor went bankrupt. A foreign sales agent signed on but found no overseas buyers. The home video market did not exist. Only two or three festivals screened it, most notably Vancouver, where it was given serious attention and extensive analysis by Tony Reif. Meanwhile, Kent, Bill and I returned to our day jobs, resigned to the consensus wisdom that it was a noble failure, a bridge too far. We chalked it up to a learning experience and/or it was not our time to shine.

It sat in my closets, basements and attics for 40 years—with three or four exceptions like playing Jon Dieringer’s Spectacle Micro Cinema in Brooklyn, The Oak Cliff Texas Theater in Dallas, and the Anthology Film Archives in Manhattan— until three years ago I got an offer to put it out on digital from Etiquette Pictures, the art film subsidiary of Vinegar Syndrome. They gave me a small advance which I used as seed money for a total overhaul of the original, which they promised to include as an extra on the DVD release of the original, if I was finished in time. To clarify, Etiquette Pictures and Vinegar Syndrome, specialize in restoring old movies and keeping the authentic nature of the original artifact. That is to say, they had more respect for it than I did.

I spent a full year reevaluating every inch of film and every second of sound. I cut out ten minutes and added three. I shot a new ending. Replaced some of the music. Polished all the visuals, using After Effects to add weather, dramatic lighting, and set decorating, also added the butterfly and the video of “Carl Samson,” the male prostitute in the auction scene, portrayed by one of my favorite DFW actors, Bryan Massey, etc.

BK: What sort of new footage did you shoot to incorporate into the already existing footage?

TH: The new ending which plays after the credits, the male prostitute at the auction scene, the butterfly, titles, and lots of minor visual effects elements with After Effects; weather, lighting, and set decoration.

BK: Is Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited a political movie, an out and out art movie, or is it both?

TH: I’m not sure about Bill and Kent, but I had political axes to grind in in the late ‘70s, and now. I am more or less the same pacifist, militantly liberal, feminist, freethinker, GLBTQ supporter, anti-authoritarian moralist. I’m soft on victimless crime and hard on exploitation of the weak by the powerful. The CIA’s MKUltra papers were declassified in ’78, I think, and I got a Xerox copy. I was super outraged over their abominable experiments with psychedelics for mind control, torture and warfare, which were shut down circa 1959, when a famous, high level US Navy colonel jumped out a window to his death after his drink was spiked with acid at a cocktail party. A year later, Timothy Leary was hired by Harvard and began clinical trials using the same drugs to heal people of neurosis and alcoholism, rehabilitate hardened convicts, and spark religious revelations in divinity students. Before the CIA working behind the scenes had Timothy fired. If they couldn’t use it to torture people, they didn’t want Timothy using it to save the world. What may seem like a digression on my part isn’t really.

I didn’t know it at the time in 1979 when we hypnotized Bill Paxton during the psyche sessions we set up to relax him so he could more easily remember childhood experiences, but the personality test we administered him had been written by Timothy Leary in the mid-1950s when Leary was an assistant prof at UC Berkeley.

In 1983 the film seemed more transgressive, a la works by Pasolini, Burroughs, Battaile; but it seems like the world has caught up more or less. One thing that was missing was mostly absent to me when I revisited the project: a spiritual element. God. Hope faith and love. Although Billy has that wonderful bit of narration during his escape into the forest, spoken from Bill Paxton’s heart about how he equates God with Nature. I took off from that line in the original and the delightful story Bill(y) tells about when he was a boy and his beloved old man used to drive him around in a vintage Rolls Royce, pretending he was the chauffeur and Bill was his boss–and added a distinct spiritual/metaphysical element that would have been missed by viewers of the original.

Hopefully, now, it’s as much a Christian film as a political film. My dream would be to see it sold at Christian book stores, but I’m not holding my breath.

It doesn’t support any political party, at least none that exist now, if I’m not mistaken. In that respect it is like Brave New World, Alphaville, or 1984. Most certainly it touches on political issues, pitting a patriarchal society against a cabal of militant feminists, but neither are all bad or all good. They’re mostly bad and a little good. They both exploit younger, disenfranchised people.

TTMR is political, psychological, spiritual, psychedelic, erotic, experimental and GLBTQ. Both political groups persecute and torment the hero. But, in the end, he is killed by a third character who is a loner who belongs to no groups. So I guess, ultimately, the message is more philosophical, existential, than political, until the new sequence after the end credits roll opens a new can of religious worms.

BK: How was the voiceover created?

TH: Very meticulously over three years, all together. Ninety-nine percent of it was done for the 1983 version. As far as the script, I kept as much of the character dialogue from Kent’s script as I could, losing about half of it ultimately. Then I wrote new dialogue that served the plot. Most of those lines occur off screen or on top of reaction shots. I hired a lip reader at first, hoping for a free lunch, only to find out several of the actors were speaking Welsh. We cast local stage actors in Austin, very few were actually British, but they could fake it pretty well. Then about half of that was replaced once I moved back to Hollywood and hooked up again with Kent Smith. We held another casting session and got a lot of Welsh and British nationals to replace some of the more questionable bits.

For the radio broadcasts, Paul Cullum wrote quite a bit of the prophetic, apocalyptic material. To be more specific: William Burroughs wrote approximately the first three or four minutes, ending with the line about fresh water sharks in the Hudson River feasting on spaniel size rats, which is heard right before Billy enters the Castle Hotel for the first time. Most of the subsequent bits were Paul’s, although Kent Smith contributed a couple of the more whimsical stories, like the Norwegian Gum-Eating Contest. I had some input on the broadcasts, especially on aspects that related directly to the plot, (which was my responsibility: keeping the story moving and continuity, so one scene didn’t contradict the next) i.e.reports of the arrest and fate of Billy’s fellow time-bomb assassins.

Some of the stories on the radio were lifted from public domain sources, like the

story of the Buddha-and-the-grapes which is heard during the main sex scene. The rest was Paul Cullum’s fault and may have been an offshoot from his newspaper column, “The Wasteland,” of which I was a fan, and which led to me bringing him into the project. Paul is also one of the voiceover actors, the bigoted British loudmouth in the first pub scene who is heard bashing American immigrants. I am the voice offering one line of pro-American counter point, which constitutes my entire feature-film oeuvre as an actor.

BK: What sort of home video release will Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited receive?

TH: TTMR will be released in the USA and English- speaking Canada by Etiquette Pictures on DVD and Blu-ray as an extra on their package which will feature their 4k transfer of the original TTM, along with other extras. I’m concentrating on the theatrical festival release of TTMR and release in foreign circuits.

BK: What do you hope audiences get out of watching Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited?

TH: A deep, rich, provocative, and entertaining experience that makes them contemplate the themes that are raised. I also hope the release will inspire people to reevaluate Bill Paxton as an auteur, adventurer, and total filmmaker.

**

A very special thanks to Tom Huckabee for agreeing to participate in this interview and to david j. moore for setting it up.

Check out the Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited Facebook page here.

Check out the Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited trailer here.

Check out the Gold-Alchemy website here.

Check out my review of Taking Tiger Mountain Revisited here.

All images courtesy of Gold-Alchemy and Tom Huckabee.